Following our report on Property118, landlords have been getting in contact and asking what they should be doing. Tax Policy Associates doesn’t, and can’t, provide tax advice – but it’s a fair question. Here’s a quick summary of how we see things:

Section 24 of the Finance (No. 2) Act 2015 amended the UK tax code to restrict landlords’ ability to deduct their mortgage interest costs from their taxable rental income.

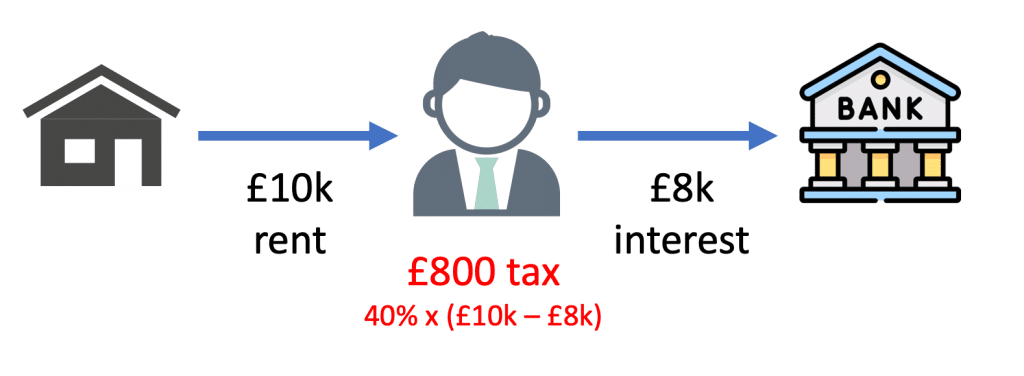

A landlord whose business looked like this in 2015:

Now looks like rather different – after tax, he’s making a loss:

That’s a huge deal for buy-to-let landlords, and it’s understandable that many are desperate for a structure that fixes the problem. There is no such structure.

There are three choices, and only three choices.

Choice 1: incorporate

Instruct a proper tax adviser, incorporate a company, and move the business to that company. The mortgage interest will then be fully deductible against the company’s corporation tax.

There, however, are several important complications:

- Your current mortgage lender is very unlikely to agree to carry your existing mortgage over to the new company. You’ll need a new mortgage, and it will almost certainly be more expensive (higher interest and higher fees). This may add up to more than the tax benefit of interest deductibility. Do the math very carefully.

- There will almost certainly be stamp duty/SDLT at up to 15% on the transfer to the company (and another 2% if you’re a non-resident).

- Some people claim that married couples can retrospectively claim to be a partnership, and escape SDLT on incorporation using the partnership rules. The recent SC Properties case makes clear this has very little likelihood of working, because of the complete lack of evidence of the married couple in question acting like partners in a business partnership :

“For these reasons we have concluded that the Partnership has no legal reality. It existed as a planning idea in the minds of the Appellants’ advisers and Mr Cooke, but had no substance beyond the forms which were completed in order for it to obtain the tax result suggested by the Appellant’s advisers.”

- There may be capital gains tax when you transfer the properties to the company. CGT incorporation relief is potentially available, but you have to demonstrate you have a “business”, something that HMRC do not always accept. Be aware that “clever” structures (such as declaring trusts, creating loans, using LLPs etc) risk blowing up incorporation relief, and costing you much more tax than they save.

- The company is taxed on its profit, with a deduction for its interest costs. You then have a second level of tax when the company returns that profit to you, as dividends, wages or (in some limited circumstances) as a capital gain. Again, you need to do the math carefully to make sure you fully take this into account.

Choice 2: don’t incorporate

Continue as you are, bearing the cost of the section 24 non-deductible interest.

Your could reduce your leverage, so you don’t make an after-tax loss (but of course you’ll then need to deploy more capital).

Choice 3: sell-up

It may be that neither of the first two options work – section 24 simply makes your rental business uneconomic. That seems to have been Osborne’s intention.

In which case, you may need to sell-up. It’s not an admission of failure – it’s an admission that investors have to adapt when circumstances change.

What is the fourth choice?

There isn’t one.

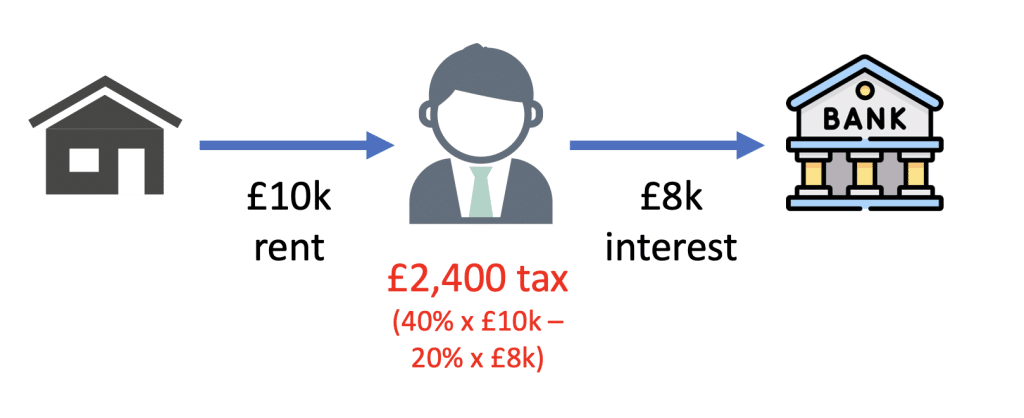

Trusts, LLPs, offshore arrangements… not only are they very likely to fail when challenged, but the consequence could be much much worse than if you’d done nothing at all. SDLT plus CGT could easily be a six figure sum. And complex structures can easily have complex, and expensive, additional tax consequences.

Whether you’re a multinational executing a £10bn M&A transaction, or a landlord considering incorporating a one-property business, the key tax question is always the same: “how much do I benefit if this goes right, and how much do I lose if this goes wrong?”.

Even if the Property118 structure probably worked (which it doesn’t!) the downside risk of it going wrong is much, much larger than the benefit.

How do I spot the cowboys?

Here are some warning signs:

Unqualified people giving tax advice

Any tax advice should come from someone at a regulated firm (accounting firm or law firm), and/or with a tax qualification such as STEP, or a Chartered Institute of Taxation or Association of Tax Technicians qualification.

I don’t want to deal with some salesman who then hires the tax adviser. I want to be speaking to the actual tax adviser.

The safest approach is to only instruct an ICAEW-regulated accounting firm or an SRA-regulated law firm. Avoid unregulated “boutiques”

“HMRC approved”

HMRC don’t approve any tax planning

“HMRC has never challenged any of our structures”

Unsurprising, if HMRC have never been properly told what precisely the scheme is. Typically promoters are careful to only discuss limited aspects of their schemes with HMRC. Rarely, if ever, is the whole structure explained.

Responds to all technical queries with confident assertions that HMRC has accepted the structure.

Again, it’s doubtful full details were given to HMRC. But, if the scheme doesn’t work technically, then any HMRC clearance is worthless, and the fact they may have sneaked it past one sleepy inspector doesn’t stop HMRC re-investigating it at any time in the next 20 years.

“Our unique system”, “our proprietary strategy”, “our IP”, etc.

I used to advise the largest businesses in the world, doing deals of many £bn. If I’d told them I planned to use anything “unique” or “proprietary”, I’d have been out the door in seconds.

When it comes to tax, sensible people do what everyone else is doing. Be boring.

Any adviser proudly touting their “unique IP” is accidentally revealing a “hallmark” that means the structure may well be disclosable to HMRC as a tax avoidance scheme.

“We have a KC opinion”

Normal people shouldn’t be doing anything so complicated and uncertain that it requires a KC opinion (I’d certainly never put myself in that position).

The fact a KC opinion was obtained is an alarm bell that something high risk is going on. That’s particularly the case if the KC opinion was obtained by the adviser for the adviser. Then you can’t rely on the KC opinion – if everything goes wrong you can’t sue the KC. Worse still, the fact the adviser obtained the KC opinion may make it harder for you to sue the adviser (as they’ll blame the KC). So a KC opinion can actually make your position worse.

“We’ve glowing testimonials from dozens of clients”

This is how a salesman talks.

No discussion of risks and downsides

Any client – whether an individual or the largest corporation – should ask two important questions of a tax adviser. What’s the result if this goes according to plan? What’s the risk if it doesn’t? And how much will it cost me if it doesn’t?

Many of these structures have a relatively small benefit (tax relief on interest) but risk a massive up-front SDLT and CGT cost. Not worth the gamble even if the odds were 70% in your favour (which they won’t be).

Pressure to go ahead/sign a contract

That’s how a (bad) double glazing salesman behaves.

“We’re fully insured”

That’s great – for them.

Professional indemnity insurance protects an adviser against being successfully sued. It’s useful to a client because it gives you assurance that you will still have someone to sue if the adviser disappears/goes bust. But it doesn’t make it easier to sue them, and it certainly isn’t your insurance..

“Your normal advisers won’t be familiar with these obscure rules”

A common tactic to pull clients away from trusted existing advisers, and often said by people who don’t in fact have any tax qualifications.

![To: jeevacation@gmail com[eevacation@gmail com]

From: Peter Mandelson

Sem: Sun 11/7/2010 2 34 57 PM

Subyect: Fwd Rio apartment

Seat to mys bank manager Gratetul tor helpful thoughts trom my chief lite adviser

Sent from ims iPad

Bevin torwarded messave

From: Peter Mander iS

Date: 7 November 2010 [4 29 12 GMI

Subject: Rio apartment

P| ag awe dpeecussed Pan consdernne a purchase of an apartmentin Rion Ttisain](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Screenshot-2026-01-31-at-21.27.15-640x360.png)

Leave a Reply to Fingernails down the blackboard… Cancel reply