There’s a problem with a lot of Left-wing tax advocacy: it identifies a political challenge, and proposes a policy aimed at solving it. But the authors believe so strongly in the policy’s righteousness that all of their time and focus is spent on advocacy, and none on analysis. They don’t speak to outside experts, don’t think about incentives and consequences, and only look at data to find support for the proposal. It’s “policy-based evidence-making”… and ultimately it doesn’t help anybody.

It would be invidious to pick on one example – but I’m going to do that anyway.

Here’s a proposal out today from the European Greens.1archive link here.

It’s a perfect illustration of my point, because of the way it jumps from identifying a political problem to a solution, without any attempt at considering how that solution would play out. And in reality, the proposal would be a disaster – in the very year the Greens pick as their exemplar, it would have cost governments billions of Euro in tax revenue.

The policy challenge

Here’s how the Greens start:

We can agree or disagree with this, but it’s undoubtedly a valid position to hold.

The conventional policy answer would be: tax capital gains at a broadly equivalent rate to labour income. That’s justified on grounds of vertical equity (the rich should pay tax at the same rate as the poor), horizontal equity (rich people making capital gains should pay tax at the same rate as rich people receiving large bonuses), and anti-avoidance (because otherwise people convert income into capital gains to achieve a lower rate).

But the Greens take a different approach.

The proposal

In other words: a 40% minimum tax on capital gains, and for listed shares it would be on gains whether realised or unrealised.

To be clear, if I buy €1,000 of shares today, and sell them next year for €2,000, then that’s obviously a €1,000 capital gain on which I’d pay tax (at a minimum of 40%). But even if I don’t sell them next year, if they’re worth €2,000 then I’d pay capital gains tax on my unrealised €1,000 gain.

There are very few countries that tax unrealised capital gains. Many people find the idea counterintuitive or unfair, but it’s supported by many economists on the basis that an unrealised gain is just as “real” as income or a realised gain. Tax specialists tend to be more cautious, worrying about the difficulty of valuing property, and the practical problems that will arise from paying out refunds when people have unrealised capital losses2If your response is “well, we won’t refund tax for capital losses”, then the policy is no longer a tax on capital gains, and instead a crude and rather random expropriation of property.

Reasonable people can certainly differ, and the Greens are absolutely not being unreasonable in seeking to tax unrealised capital gains.

Reasonable people can also disagree with a blanket 40% rate. Better to track the rate of tax on income (or, more sensibly, dividends). If capital gains is taxed at a higher rate than dividends then people will take dividends instead; if it’s lower (as is generally the case now), they’ll manufacture gains instead of taking dividends. The solution is surely to unify the rate, not to pick 40%.

These are not my point. There are two much bigger issues.

Fudging the data

You’d expect any credible tax policy proposal to be accompanied by some figures – ideally an estimate of the revenue consequences.

Here’s what the Greens give us:

There are two massive problems with this.

First, the detail is all wrong, because only a small percentage of the shareholders of these four companies will be taxed by the proposal:

- any EU proposal is obviously only going to tax the capital gains of EU citizens. What percentage of these four companies’ shareholdings is held by EU citizens? I expect not much. Most of the shareholders will be outside the EU (certainly BP and Exxon, and probably also Shell).

- The majority of the EU shareholders will be institutions rather than individuals. The OECD has estimated that only 18% of shareholdings in publicly listed companies are held by private companies and individuals.3See this document, the sixth bullet point on page 6 and Figure 2 on page 12. I’m assuming the Greens are not proposing taxing pension funds and other institutional investors – pension funds are generally exempt from tax, and institutional investors will either be exempt from tax (e.g. OEICs) or taxed on a mark-to-market basis already (e.g. investment banks).

So the true figure will probably be closer to $14bn.

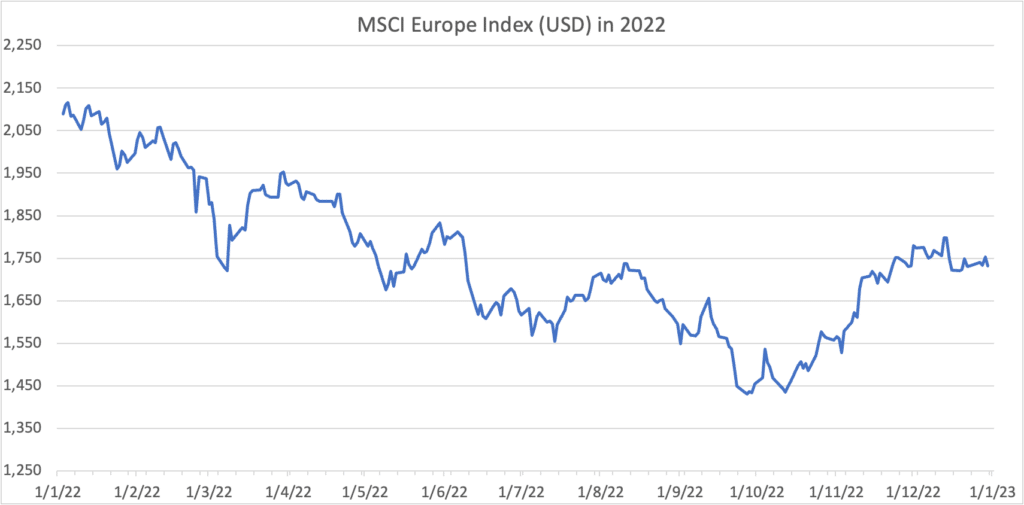

Second, the big picture: it’s extraordinarily selective to pick four companies who’ve had a good energy crisis. The proposal applies to all listed companies… so what was the total gain in market capitalisation of all listed European equities in 2022?

It was negative.4I used the MSCI Europe index captures about 85% of European equities and is therefore a reasonable way to answer the question; there will be other approaches, but the answer will likely be the same… 2022 was a bad year for equities. Historical data from investing.com.

If this proposal had been adopted in 2022, it would have cost European governments money.

The $140bn figure is embarrassing on every level.

It’s the epitome of policy-based evidence-making. They’ve started with the idea they want to tax capital gains more heavily, and then gone hunting for some numbers that support the idea. Any neutral enquiry – “hmm, I wonder what the effect of the policy would have been in 2022” – would led to the conclusion that the policy would have cost governments €billions in 2022.

Ignoring the incentives

This isn’t a proposal to tax unrealised capital gains – it’s a proposal to tax unrealised capital gains of listed shares.

That’s a huge problem – because it creates a powerful incentive for taxpayers (and particularly the very wealthy) to not hold listed shares.

Some might create avoidance structures – e.g. establishing their own private SPV/fund in a non-EU country, and have that SPV/fund acquire listed equities. Others would simply reallocate investments to listed debt (e.g. high yield bonds), unlisted equities, real estate, private funds, and other asset classes. And you’d certainly see a decline in entrepreneurs listing their private companies.

All of which means the tax yield would be much less than expected, with the potential for undesirable non-tax consequences too (I personally think we benefit from having successful companies listed rather than private).

A good rule of thumb for tax policy is: don’t tax something in a way that depends upon a feature which has no economic reality, and can easily be changed. No baker in the UK puts chocolate on their gingerbread men covered in chocolate, other than two spots for eyes – because having more chocolate than that triggers 20% VAT. Whether a company is listed is, in many cases, about as economically relevant as chocolate eyes. It’s a terrible basis for taxing shareholders in the company.

I’m unconvinced it’s a good idea to tax unrealised capital gains. But if you disagree, it’s imperative you tax all unrealised capital gains.

How to do better

Three simple suggestions:

- All tax policy proposals should be “red teamed“. People who weren’t involved in the design of the proposal should sit down and think about how they, as a taxpayer, would react to it. What are their incentives? What are the loopholes?

- Europe is blessed with thousands of tax academics and tax practitioners (in government and the private sector). It’s madness to propose a tax policy without speaking to some of them. I’m certain any tax academic or practitioner would immediately have identified the two problems above.

- Finally, don’t confuse means with ends. The end result here should be fair taxation of capital gains, and the question should have been: how do we best achieve that? But I suspect that this project started with a desire to tax unrealised capital gains, and that led to everything else.

Image by Stable Diffusion – “a calculator violently exploding in a massive fireball, dramatic, award winning, pop art, roy lichtenstein”

- 1

- 2If your response is “well, we won’t refund tax for capital losses”, then the policy is no longer a tax on capital gains, and instead a crude and rather random expropriation of property

- 3See this document, the sixth bullet point on page 6 and Figure 2 on page 12

- 4I used the MSCI Europe index captures about 85% of European equities and is therefore a reasonable way to answer the question; there will be other approaches, but the answer will likely be the same… 2022 was a bad year for equities. Historical data from investing.com.

12 responses to “Why the Left struggles with tax policy”

As a general thought, presumably a large chunk of the issue here is the sheer complexity of most tax regimes beyond income tax. Anything that needs vast volumes of leather bound books (or their modern equivalent) to interpret is just too hard to re-engineer in a way that can be captured with a catchy slogan. Both sides of politics are equally guilty on this one. Unfortunately this leads to loopholes, which need to be closed, which leads to more complexity, which leads to an ourobos of tax law. And a system that is complex rewards the people who can move assets and income between countries and ultimately just adds to the complexity and cost for smaller taxpayers….

Without indexation, gains on assets held for the long term do suffer an over-taxing effect, which is used around the world to justify lower rates on capital gains.

Which means gains held for the short-term are under-taxed.

The answer is indeed indexation – from 1988 to 1997 the UK had the most sensible CGT anywhere.

Destroyed by Gordon Brown who had an instinct to fiddle and micro-incentivise.

And no subsequent chancellor has shown any interest in removing tax anomalies in order to “get out of the way”, comparable to those in the 1980s.

How do we get any political party to embrace that drive for removal of distortions in all taxes?

A “red team” approach to EU policy proposals, during a stand still period of day 10 weeks after publishing a draft and before formally proposing a measure would be a major innovation in EU policy making generally

To be fair, there are very few politicians who would want their proposal to be subject to an official process of public scrutiny by experts, paid to find holes in it…

Very thoughtful article. There are many calls for taxation along these lines, cherry picking the examples that suit the argument. Should a political party that gained power on the basis of these proposals try to put them into practice they would then discover either that it didn’t raise the claimed tax revenues or that it brought into play the other disincentives and detriments the article points out. Not least would be the adverse effect on vast holdings in pension funds which few members of the public realise they rely on. In short it’s likely a populist vote attracting ruse.

I think the taxation of personal capital gains certainly needs looking at and I’d definitely support the re-introduction of indexation relief – maybe based on a lower index than RPI.

On the corporate side CGs are very rare given SSE and rollover and perhaps that is appropriate, but personal CGT has been messed around with for a generation. Give aways like taper relief seem to have been baked into the system when the rates came down dramatically and perhaps we now need a separate genuinely progressive series of rates of CGT with separate rates or scales for business and non-business to stop the squealing from the “wealth creators”? I’m not sure merely aligning with the marginal rate of income tax would work, and the severe planned reduction in the annual exemption seems punitive for those making very modest one-off gains.

As an aside, although capital gains are currently the whipping boy of choice, will anything be done about the real avoidance culture that is extraction of dividends through small businesses to the owner and their family (usually spouse)? Everything that they have tried (hello Arctic solutions! and the attempted dividend fix of 2003-5 ish) has failed. Do we need to see basically an extension of IR35 to stop this real abuse.

How many of us know people who milk the system this way – tiny sub NIC salary paid to supposedly “employed” spouse, along with dividends, and hey presto child benefit thresholds met and 30 hours of free childcare as well! A kick in the teeth to those struggling to get by at the lower end on PAYE!

IMO nothing can really change (except at the margins) whilst gap between tax on labour and dividends/gains is so large

Rather than fiddle with dividend and CGT rates, the best solution is to allow spouses to combine their personal allowances and tax thresholds.

Unfortunately that’s unlikely when politicians ignore the benefits of stay at home parents and the harm to children of factory childcare provision.

that would cost a fortune…

Very apposite and a regular feature of such proposals is the disconnect with the real world of tax, business and possibly even taxpayers.

Judith Freedman wrote a few years ago about administrability. Very much on point here.

Tax administration should be central to the tax design process, writes Professor Judith Freedman (Oxford University).

It may seem that when designing a tax system there is a natural order of things. First, we must decide on the aims, principles and underlying legal concepts. Only then do the practicalities need to be considered. But tax design does not work quite like that. Practicalities are more central than this description implies. Many accept that a broad concept of optimal taxation should include considerations such as administrative and compliance costs (Mirrlees Review, Tax by Design, page 38). I go further and argue that administrability should be central to the tax design process. Three of Adam Smith’s four famous canons of taxation are largely about administration. Tax administration is not an afterthought but goes to the heart of which concepts should be utilised.

https://www.taxjournal.com/articles/-tax-administration-shaping-tax-reform-does-employment-status-matter-for-tax-

Great piece, but surprised that an article on capital gains has no discussion of indexation allowances. I know it’s not central to the specific discussion here, but any in-depth dive into how to tax capital gains should include some thought on whether a nominal capital gain of an asset, which has no real gain (ie after allowing for inflation indexation) should be taxed at all.

That’s a great point. It’s a problem with the current UK regime, but has been masked by the low rate and a long period of low inflation. Raising the rate makes it IMO hard to defend not allowing indexation. And taxing unrealised gains without indexation would be unjust.