The two biggest tax-cutting Conservative Chancellors in British history both increased capital gains tax – and for good reasons. Jeremy Hunt should follow them, and raise £8bn.

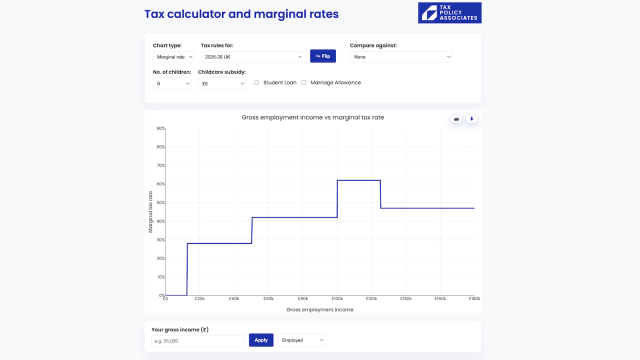

Here’s the current situation: someone earning £50k pays income tax at a marginal rate of 40%; someone earning £150k pays a marginal rate of 45%. But the same person making a capital gain pays nothing on the first £12,300 of gain, and only 20% on the rest. This is a problem for several reasons:

- It’s inequitable that a type of income received mainly by the wealthy🔒 is taxed less than other types of income (and particularly employment income). “Mainly” understates the case – HMRC statistics show that over half of all taxable gains are received by only 5,000 people:

- The difference between income tax and capital gains tax rates is so great that it creates a powerful incentive to shift income into capital. This can be done on a small level by an individual investor – for example, if you hold shares in a company or mutual fund about to pay a large dividend, then that dividend would be taxed at a top marginal rate of 39.35%. If instead, you sell the shares after the dividend is declared (but before it is paid) then you’re receiving the value of the dividend (embedded in the share price), but only paying 20% capital gains tax. It can be done on a much larger scale by a large investor, or indeed the owner of a sizeable private company.

- On a larger scale, a good chunk of the private funds industry gives its executives “carried interest” in its funds, which makes up the majority of their remuneration. This is usually subject to capital gains tax at 28% (a higher rate than usual, but still considerably less than the 39.35% dividend rate). That is inequitable. It also creates a distortion where the precise nature of an asset management business can have a dramatic effect on the tax paid by its executives1

- And finally, there’s a £12,570 personal allowance for income tax – anything below that isn’t taxed. Fair enough. But then there’s another completely separate £12,300 allowance for capital gains. Shouldn’t there be just one allowance for everything? (Perhaps with a small de minimis, say £1,000, to remove the need for filing for small gains.) Otherwise it’s just a £2.5k giveaway to investors, and one which is widely gamed.

To my mind, the case for change is irresistible.

How did we get into this mess?

Today’s CGT problems are nothing compared to how things were before 1962, when capital gains were completely untaxed. So when you see 90%+ top rates of income tax in the 1950s, you’re safe to assume that the properly wealthy took most of their returns as capital gain, and paid no tax at all. The halcyon days of progressive taxation it was not.2

Then in 1962 the second most spectacularly tax-cutting Chancellor in British history, Anthony Barber, introduced (when he was Financial Secretary to the Treasury3) a “speculative gains tax” that taxed some short-term capital gains as income (countering some of the most obvious avoidance schemes that were around at the time). Three years later, an actual capital gains tax was introduced, at a flat rate of 30%4. Again much less than the rate of tax on normal income – I’m not clear why.

The rate stayed at 30% for 20 years, with an “indexation allowance” introduced in 1982 so that inflationary gains wouldn’t be taxed. And then the absolutely most spectacularly tax-cutting Chancellor in British history, Nigel Lawson, in the absolute most tax cutting Budget in British history, increased the rate in 1988, so it applied at whatever the taxpayer’s marginal rate was. His explanation couldn’t have been clearer:

There it stayed throughout the Blair premiership.5 Then one of Gordon Brown’s big mistakes – he and Alistair Darling cut the rate to 18% in 2008. George Osborne pushed it back up to 28% in his first Budget in 2010; then cut the rate to 20% (in most cases) in 2016.

This leaves us today with the problem that Lawson thought he’d solved: a capital gains tax rate that’s often much lower than the income tax rate.

What’s the answer?

In short:

- Go back to the Lawson solution, with capital gains charged at the same marginal rate as income.6

- One exception: just as dividends are taxed at a somewhat lower rate than other income (to reflect the fact they’re paid out of a company’s post-tax profits), so capital gains in shares should be taxed at a somewhat lower rate. The obvious answer is to simply apply the relevant dividend rate.7

- Merge the income tax and CGT personal allowances. Once the allowance is used, all capital gains should be taxable (with say a £1,000 de minimis to prevent taxpayers and HMRC having the hassle of dealing with small gains).

- If we keep Business Asset Disposal Relief then there should be little/no impact on small businesses (which is where much of the debate has been around changing CGT rates, even though CGT is mostly paid elsewhere).

- Care also needs to be taken to introduce any increase in CGT rates very quickly, ideally overnight. Otherwise, people will accelerate gains to beat the rate increase. If an incoming Labour Government plans to increase the rate then it may be wise to pre-announce it ahead of a Budget, and very soon after the election, with the new rate applying retrospectively from the date of the announcement.

None of this is very controversial in tax policy circles. Rishi Sunak asked the Office of Tax Simplification to look into problems with CGT, and equalising rates and reducing the allowance were their key recommendations. Sadly, Rishi shelved it.

There is a debate to be had as to whether, if we’re returning to the higher rates of the 80s and 90s, we should return to having an indexation allowance so that inflationary gains aren’t taxed. The argument for: it’s unfair to tax a gain that isn’t real. The argument against: we tax inflationary elements of income returns (e.g. interest on a loan, bond or bank account is fully taxed). However the CGT position is different: the indexation allowance is solely applied to capital which was locked up/put at risk. So on balance, I would support the reintroduction of an inflation allowance (or, alternatively, follow the Mirrlees Review recommendation of giving an allowance equal to the risk-free return on government bonds).8

Would increasing the rate of CGT adversely affect business investment?

There is no evidence for that. IFS research has found that the current low CGT rates save plenty of tax for investors, but don’t increase investment.

How much would it raise?

In 2020-21, CGT raised a record £14.3bn. I estimate an additional £7bn would have been raised that year if CGT rates had been equalised with income tax and dividend rates9. That’s on the basis of a simple static analysis applied to HMRC data on how much gain is attributable to the various different asset types. It’s quite a lot less than some other estimates out there, very possibly because I am equalising at the dividend tax rate, not the income tax rate. And it would be sensible and just to reintroduce the “indexation allowance” that prevents CGT from taxing illusory gains that are wiped out by inflation.

HMRC estimated🔒 that in 2020-21 the £12,300 annual allowance cost £900m.

So overall we are looking at approximately £8bn of revenues. Dynamic effects will reduce this, but I don’t expect by much provided sensible steps are taken to protect the base.

Footnotes

for example Anthony managing “managed accounts” for several large clients can’t have carried interest; Amelia managing a private fund for several large clients can. That’s an undesirable and inefficient distortion. ↩︎

To return to a recent theme: never, ever, look at tax rates in isolation – the question is *what* the rates apply to, and what they *don’t*. ↩︎

I got this muddled in my first draft, and said Barber was Chancellor in 1962, which he wasn’t until 1970 ↩︎

I’m skipping over the taper, entrepreneur’s relief etc ↩︎

The trust rate would also have to be increased. ↩︎

If you don’t buy the logical argument for this, then accept the pragmatic one: if the CGT rate is higher than the dividend income tax rate, people will shift from gains into dividends. That’s precisely what happened in the post-Lawson era, with people using scrip dividends for this purpose. ↩︎

There’s a good discussion of this in Arun Advani’s paper here🔒. ↩︎

Much of the revenue would be income tax, as people cease bothering to convert income to gains ↩︎

Leave a Reply