Fujitsu has indicated that it’s willing to help compensate victims of the Post Office scandal. But will this be a small voluntary contribution, or can the Post Office sue Fujitsu to recover some of the £1bn cost of the Horizon scandal? We’ve spoken to leading commercial litigation lawyers, and we’re concerned that the Post Office’s own failures mean that there is little legal prospect of recovering the £1bn from Fujitsu in the courts.

Ministers have said the Government will pursue Fujitsu for its role in developing the faulty Horizon system; the Justice Secretary has said that Fujitsu should “pay a fortune”. Many people would agree. But can the Post Office make a claim?

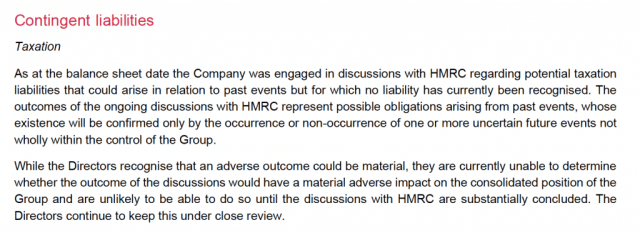

We have reviewed Post Office annual reports and accounts, and other publicly available documentation, and can see no mention of any potential claim against Fujitsu to recover some of its Horizon losses. This is surprising given the £1bn+ cost to the Post Office of the scandal, the fact that the ultimate cause was faulty software provided by Fujitsu, and the evidence that Fujitsu personnel were complicit.1 Horizon is still being utilised by the Post Office and we understand that the software is still producing faults.

The obvious route for any claim by the Post Office would be breach of contract.2 Fujitsu’s staff may also have been negligent, or even have deceived the Post Office, both of which could give rise to a claim in tort (the law of civil wrongs). Whether any such claim could be successfully made by the Post Office is undoubtedly a difficult question, particularly that the Post Office appears to have been complicit in Fujitsu’s failings. Establishing whether Fujitsu is liable, the quantum of its loss, questions of causation, contributory negligence, mitigation etc, would require an extremely lengthy and complex investigation and analysis, and any legal dispute would undoubtedly occupy the courts for years.3

Even if the Post Office concluded that its prospects of success were limited, we believe a normal company in that position would make a claim to protect its position, and that of its shareholders.4

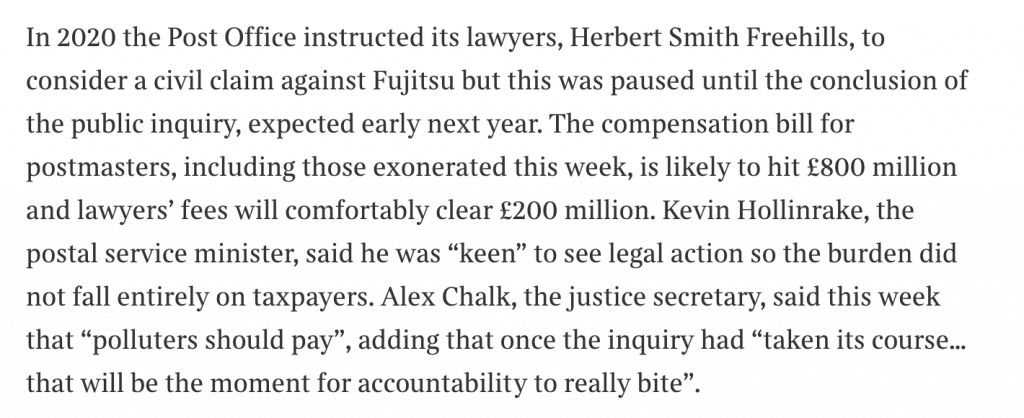

Last week, the Times reported that:

The problem is that 2020 may well have been too late. The Post Office may be time-barred.5

The Limitation Act – the basic position

Claims will become statute-barred under the Limitation Act if an action is not started within the relevant period:

- For contract claims this period is six years from the date of the breach of contract, but this can be extended to run from the time when the claimant realised or ought to have been aware that the claim existed.

- For tort claims (i.e. negligence, and the tort of deceit and other economic torts) the period is six years from the date of the loss, potentially extended to three years from the date on which the claimant had the requisite knowledge and the right to bring such an action.6

- For negligence there is an absolute long-stop date of fifteen years from the date of the breach of duty.

- However, all limitation periods are extended if there is fraud or concealment: the limitation period starts to run from the date the fraud or concealment is discovered.

Let’s leave aside Fujitsu’s technical failures in building Horizon, because whilst these no doubt resulted in significant loss for the Post Office, the £1bn relates to the persecution of the postmasters, and the many costs that have resulted from that (the years of legal disputes, the compensation itself, the cost of the Inquiry, etc). Any prospect of recovering a significant part of this £1bn from Fujitsu requires establishing that Fujitsu personnel were responsible for the actual persecution of postmasters.7

The most serious actions of Fujitsu appear to be the evidence of its employees, Gareth Jenkins and Anne Chambers, in the trials of Lee Castleton, Seema Misra and others, who assured courts that Horizon was robust when they knew full well it was not. These trials took place in 2007 and 2010. Similar evidence was given in other trials until 2013.

That all stopped because, in 2013, the Post Office was advised by barrister Simon Clarke that there was a serious problem with Jenkins’ evidence:

Also in 2013, Second Sight published an interim report⚠️ identifying serious bugs in Horizon.

It is plausible, even likely, that the Post Office was aware of these issues well before 2013, but in our view 2013 is the latest date that the limitation period clock will have started ticking. That means the limitation period ended in 2019 at the latest.8

Standstill agreements

In practice it’s fairly common for claims to be started after the normal limitation period has expired. Where, as may have been the case here, the nature and fact of the claim is known but the extent of it is not, parties typically enter into a “standstill agreement” at an early stage. The limitation period then stops running.9

We infer from the report in The Times that the Post Office entered into a standstill agreement with Fujitsu at some point around 2020. The Post Office would be able to claim against Fujitsu on the basis of how the position was in 2020, notwithstanding the amount of time that has passed since then (and waiting until the Inquiry has reported its conclusions would be sensible).

However if that the limitation period ended in 2019 (or earlier), then any 2020 standstill agreement was too late, and Fujitsu will be able to argue that the limitation period has expired.10 11

Can the Government sue Fujitsu?

It is unlikely but possible that the Government was party to the Post Office’s contract with Fujitsu, or was given rights under that contract. In that case the Government might be able to bring a claim itself; however it would again be out of time unless a standstill agreement was signed.

Otherwise we see no basis for the Government bringing a claim in contract or tort – although of course it is possible there is some unique factor here which we are missing.

Can the Government force Fujitsu to pay?

In principle, Parliament could pass an Act requiring Fujitsu to pay up. This is, however, not how liberal democracies normally behave.

A more normative way to achieve the same result would be for the Government to require that Fujitsu make a “voluntary” contribution to the costs of the scandal, or be barred from Government contracts. Fujitsu is a “key strategic supplier” to Government and has been awarded 101 new government contracts worth over £2bn since 2019.

Either approach could have adversely impact the UK’s relationship with Japan; Japan might even be able to point to a breach of an international treaty (e.g. the UK/Japan Trade and Cooperation Agreement or WTO GATS).12

Of course the most consensual outcome would be the one that Fujitsu has suggested, involving Fujitsu doing the right thing (whether out of principle or pragmatism), and making a genuinely voluntary contribution without any action of Government. We are not aware of any precedent for a company acting in this matter, but these are extraordinary circumstances. The question then is whether Fujitsu would make be making a direct contribution to the £1bn bill, or (as many people might welcome) direct compensation payments to postmasters on top of, and not reducing, the compensation they are already receiving from the Post Office and the Government.

The key questions

We believe these are some of the key questions:

- Has the Post Office signed a standstill agreement with Fujitsu?

- If it did – when? And why isn’t this mentioned in the Post Office’s annual reports and accounts?

- If not, why not? And does that mean there is now no possibility of a claim against Fujitsu?

- If it was as late as 2020, then why was the matter left so long, given the grave potential consequences of delay?

- Does the Government have a potential claim itself which is not time-barred? If so, what?

In normal circumstances these would be commercially sensitive questions on which we would not expect a company to comment. However, given the public and political interest, we feel the Government should require the Post Office to provide a clear statement on these matters.

Many thanks to AP for the initial draft of this article and to J for his invaluable litigation input. This article also benefited from review by K, a former general counsel of a FTSE 100 company.

Footnotes

There are an excellent series of articles here on what technically went wrong. ↩︎

We have not reviewed the contract between the Post Office and Fujitsu, but it would be surprising if so faulty a system was within contractual specifications. ↩︎

Fujitsu’s UK accounts don’t reveal any relevant liabilities, although that tells us no more than that Fujitsu (and/or their auditors) do not think liability is likely. ↩︎

Section 172 Companies Act 2006 requires that a director’s overriding fiduciary duty is to “act in the way he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole”. Section 172 also sets out a list of non-exhaustive factors which a director must consider while evaluating what would be likely to “promote the success of the company”. ↩︎

This article does not discuss the actual contractual position, only the limitation period position. Generally in IT contracts there is a defects liability period after “completion” – typically 12 to 24 months for the contractor to remedy glitches at its own cost. If the glitches remain then a new contractor can be instructed to perform remedial action at the original contractor’s cost. However the contract is commercially confidential, and so any analysis of the contractual position would be pure speculation. This article therefore focusses on the limitation period point. ↩︎

This is a considerable simplification of an extremely complex legal position – see, for example, this excellent blog from the late David Sears QC. ↩︎

In other words, we see no way that the jailing of innocent people can be said to be a “reasonably foreseeable” consequence of the IT failures, let alone in the “contemplation of the parties” when the contract was agreed. Failed IT projects don’t usually lead to innocent people being jailed. ↩︎

Unless either (1) a longer time period was agreed in the contract, which is theoretically possible but unlikely, or (2) the Post Office can point to fraud by Fujitsu, e.g. in what we assume must have been lengthy correspondence between the parties over many years. ↩︎

You might wonder why a defendant would ever agree to such a document. That’s because the alternative is the claimant commencing a court action, and then applying for it to be stayed. The courts would likely be unamused by a defendant whose failure to sign a standstill created so unnecessary a use of court time, and therefore a sensible defendant agrees to a standstill (with the additional advantage that a court filing is public; a standstill is private). In this case, we would assume here there was no court filing and stay, or that would have become public by now. ↩︎

There is one further way the limitation period could be extended – the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978. This says, very broadly, that if two people are liable to pay damages, but one actually pays, then they can recover a contribution from the other. The important thing is that a two year limitation period starts from the date the damages are paid. So if the Post Office is paying damages today then, on the face of it, it could have two years to claim a contribution from Fujitsu. However much of the compensation is being paid by the Government, not the Post Office; and the compensation paid by the Post Office is more political than legal (for example limitation period points are not being taken). And the Act wouldn’t be applicable to the Post Office’s own considerable costs/losses (aside from having to pay compensation). ↩︎

If the Post Office’s lawyers at the time didn’t advise it to agree a standstill then there may also be a question as to whether the Post Office has an action in negligence against them. Many thanks to G for spotting this point. ↩︎

We have not looked into these issues; a serious analysis would require input from a trade law specialist. ↩︎

Leave a Reply